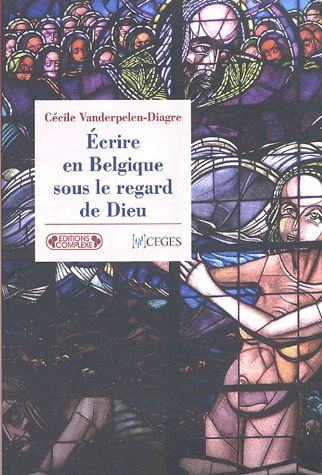

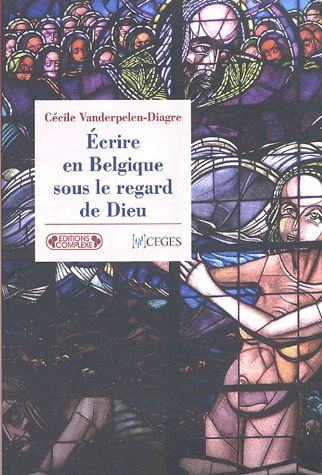

Recension: le livre de cécile Vanderpelen-Diagre sur la littérature catholique belge dans l’entre-deux-guerres

Script du présentation de l’ouvrage dans les Cercles de Bruxelles, Liège, Louvain, Metz, Lille et Genève

Recension : Cécile Vanderpelen-Diagre, Écrire en Belgique sous le regard de Dieu, éd. Complexe / CEGES, Bruxelles, 2004.

Dans son ouvrage majeur, qui dévoile à la communauté scientifique les thèmes principaux de la littérature catholique belge de l’entre-deux-guerres, Cécile Vanderpelen-Diagre aborde un continent jusqu’ici ignoré des historiens, plutôt refoulé depuis l’immédiat après-guerre, quand le monde catholique n’aimait plus se souvenir de son exigence d’éthique, dans le sillage du Cardinal Mercier ni surtout de ses liens, forts ou ténus, avec le rexisme qui avait choisi le camp des vaincus pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale.

Dans son ouvrage majeur, qui dévoile à la communauté scientifique les thèmes principaux de la littérature catholique belge de l’entre-deux-guerres, Cécile Vanderpelen-Diagre aborde un continent jusqu’ici ignoré des historiens, plutôt refoulé depuis l’immédiat après-guerre, quand le monde catholique n’aimait plus se souvenir de son exigence d’éthique, dans le sillage du Cardinal Mercier ni surtout de ses liens, forts ou ténus, avec le rexisme qui avait choisi le camp des vaincus pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale.

Pendant plusieurs décennies, la Belgique a vécu dans l’ignorance de ses propres productions littéraires et idéologiques, n’en a plus réactivé le contenu sous des formes actualisées et a, dès lors, sombré dans l’anomie totale et dans la déchéance politique : celle que nous vivons aujourd’hui. Plus aucune éthique ne structure l’action dans la Cité.

Le travail de C. Vanderpelen-Diagre pourrait s’envisager comme l’amorce d’une renaissance, comme une tentative de faire le tri, de rappeler des traditions culturelles oubliées ou refoulées, mais il nous semble qu’aucun optimisme ne soit de mise : le ressort est cassé, le peuple est avachi dans toutes ses composantes (à commencer par la tête...). Son travail risque bien de s’apparenter à celui de Schliemann : n’être qu’une belle œuvre d’archéologue. L’avenir nous dira si son livre réactivera la “virtù” politique, au sens que lui donnaient les Romains de l’antiquité ou celui qui entendait la réactiver, Nicolas Machiavel.

“Une littérature qui a déserté la mémoire collective”

Dès les premiers paragraphes de son livre, C. Vanderpelen-Diagre soulève le problème majeur : si la littérature catholique, qui exigeait un sens élevé de l’éthique entre 1890 et 1945, a cessé de mobiliser les volontés, c’est que ses thèmes “ont déserté la mémoire collective”. Le monde catholique belge (et surtout francophone) d’aujourd’hui s’est réduit comme une peau de chagrin et ce qu’il en reste se vautre dans la fange innommable d’un avatar lointain et dévoyé du maritainisme, d’un festivisme abject et d’un soixante-huitardisme d’une veulerie époustouflante. Aucun citoyen honnête, possédant un “trognon” éthique solide, ne peut se reconnaître dans ce pandémonium. Nous n’échappons pas à la règle : né au sein du pilier catholique parce que nos racines paysannes ne sont pas très loin et plongent, d’une part, dans le sol hesbignon-limbourgeois, et, d’autre part, dans ce bourg d’Aalter à cheval sur la Flandre occidentale et orientale et dans la région d’Ypres, comme d’autres naissent en Belgique dans le pilier socialiste, nous n’avons pas pu adhérer (un vrai “non possumus”), à l’adolescence, aux formes résiduaires et dévoyées du catholicisme des années 70 : c’est sans nul doute pourquoi, en quelque sorte orphelins, nous avons préféré le filon, alors en gestation, de la “nouvelle droite”.

L’époque de gloire du catholicisme belge (francophone) est oubliée, totalement oubliée, au profit du bric-à-brac gauchiste et pseudo-contestataire ou de parisianismes de diverses moutures (dont la “nouvelle droite” procédait, elle aussi, de son côté, nous devons bien en convenir, surtout quand elle a fini par se réduire à son seul gourou parisien et depuis que ses antennes intéressantes en dehors de la capitale française ont été normalisées, ignorées, marginalisées ou exclues). Cet oubli frappe essentiellement une “éthique” solide, reposant certes sur le thomisme, mais un thomisme ouvert à des innovations comme la doctrine de l’action de Maurice Blondel, le personnalisme dans ses aspects les plus positifs (avant les aggiornamenti de Maritain et Mounier), l’idéal de communauté. Cette “éthique” n’a plus pu ressusciter, malgré les efforts d’un Marcel De Corte, dans l’ambiance matérialiste, moderniste et américanisée des années 50, sous les assauts délétères du soixante-huitardisme des années 60 et 70 et, a fortiori, sous les coups du relativisme postmoderne et du néolibéralisme.

L’exigence éthique, pierre angulaire du pilier catholique de 1884 à 1945, n’a donc connu aucune résurgence. On ne la trouvait plus qu’en filigrane dans l’œuvre de Hergé, dans ses graphic novels, dans ses “romans graphiques” comme disent aujourd’hui les Anglais. Ce qui explique sans doute la rage des dévoyés sans éthique — viscéralement hostiles à toute forme d’exigence éthique — pour extirper les idéaux discrètement véhiculés par Tintin.

Les imitations serviles de modèles parisiens (ou anglo-saxons) ne sont finalement d’aucune utilité pour remodeler notre société malade. C. Vanderpelen-Diagre, qui fait œuvre d’historienne et non pas de guide spirituelle, a amorcé un véritable travail de bénédictin. Que nous allons immanquablement devoir poursuivre dans notre créneau, non pour jouer aux historiens mais pour appeler à la restauration d’une éthique, fût-elle inspirée d’autres sources (Mircea Eliade, Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Walter Otto, Karl Kerenyi, etc.). Il s’agit désormais d’analyser le contenu intellectuel des revues parues en nos provinces entre 1884 et 1945 au sein de toutes les familles politiques, de décortiquer la complexité idéologique qu’elles recèlent, de trouver en elles les joyaux, aussi modestes fussent-ils, qui relèvent de l’immortalité, de l’impassable, avec lesquels une “reconstruction” lente et tâtonnante sera possible au beau milieu des ruines (dirait Evola), en plein désert axiologique, où qui conforteront l’homme différencié (Evola) ou l’anarque (Jünger) pour (sur)vivre au milieu de l’horreur, dans le Château de Kafka, ou dans labyrinthe de son Procès.

Les travaux de Zeev Sternhell sur la France, surtout son Ni gauche, ni droite, nous induisaient à ne pas juger la complexité idéologique de cette période selon un schéma gauche/droite trop rigide et par là même inopérant. Dans le cadre de la Belgique, et à la suite de C. Vanderpelen-Diagre et de son homologue flamande Eva Schandervyl (cf. infra), c’est un mode de travail à appliquer : il donnera de bons résultats et contribuera à remettre en lumière ce qui, dans ce pays, a été refoulé pendant de trop nombreuses décennies.

La “Jeune Droite” d’Henry Carton de Wiart

Pour C. Vanderpelen-Diagre, les origines de la “révolution conservatrice” belge-francophone, essentiellement catholique, plus catholique que ses homologues dans la France républicaine, plus catholique que l’Action Française trop classiciste et pas assez baroque, se trouvent dans la Jeune Droite d’Henry Carton de Wiart (1869-1951), assisté de Paul Renkin et de l’historien arlonnais germanophile Godefroid Kurth, animateur du Deutscher Verein avant 1914 (le déclenchement de la Première Guerre mondiale et le viol de la neutralité belge l’ont forcé, dira-t-il, de « brûler ce qu’il a adoré » ; pour un historien qui s’est penché sur la figure de Clovis, cette parole a du poids...). La date de fondation de la Jeune Droite est 1891, 2 ans avant l’encyclique Rerum Novarum. La Jeune Droite n’est nullement un mouvement réactionnaire sur le plan social : il fait partie intégrante de la Ligue démocratique chrétienne. Il publie 2 revues : L’Avenir social et La Justice sociale. Les 2 publications s’opposent à la politique libéraliste extrême, prélude au néo-libéralisme actuel, préconisée par le ministre catholique Charles Woeste. Elles soutiennent aussi les revendications de l’Abbé Adolf Daens, héros d’un film belge homonyme qui a obtenu de nombreux prix et où l’Abbé, défenseur des pauvres, est incarné par le célèbre acteur flamand Jan Decleir.

Pour C. Vanderpelen-Diagre, les origines de la “révolution conservatrice” belge-francophone, essentiellement catholique, plus catholique que ses homologues dans la France républicaine, plus catholique que l’Action Française trop classiciste et pas assez baroque, se trouvent dans la Jeune Droite d’Henry Carton de Wiart (1869-1951), assisté de Paul Renkin et de l’historien arlonnais germanophile Godefroid Kurth, animateur du Deutscher Verein avant 1914 (le déclenchement de la Première Guerre mondiale et le viol de la neutralité belge l’ont forcé, dira-t-il, de « brûler ce qu’il a adoré » ; pour un historien qui s’est penché sur la figure de Clovis, cette parole a du poids...). La date de fondation de la Jeune Droite est 1891, 2 ans avant l’encyclique Rerum Novarum. La Jeune Droite n’est nullement un mouvement réactionnaire sur le plan social : il fait partie intégrante de la Ligue démocratique chrétienne. Il publie 2 revues : L’Avenir social et La Justice sociale. Les 2 publications s’opposent à la politique libéraliste extrême, prélude au néo-libéralisme actuel, préconisée par le ministre catholique Charles Woeste. Elles soutiennent aussi les revendications de l’Abbé Adolf Daens, héros d’un film belge homonyme qui a obtenu de nombreux prix et où l’Abbé, défenseur des pauvres, est incarné par le célèbre acteur flamand Jan Decleir.

Henry Carton de Wiart, alors jeune avocat, réclame une amélioration des conditions de travail, le repos dominical pour les ouvriers, s’insurge contre le travail des enfants, entend imposer une législation contre les accidents de travail. Il préconise également d’imiter les programmes sociaux post-bismarckiens, en versant des allocations familiales et défend l’existence des unions professionnelles. Très social, son programme n’est pourtant pas assimilable à celui des socialistes qui lui sont contemporains : Carton de Wiart ne réclame pas le suffrage universel pur et simple, et lui substitue la notion d’un suffrage proportionnel à partir de 25 ans, dans un système de représentation également proportionnelle.

En parallèle, Henry Carton de Wiart s’associe à d’autres figures oubliées de notre patrimoine littéraire et idéologique, Firmin Van den Bosch (1864-1949) et Maurice Dullaert (1865-1940). Le trio s’intéresse aux avant-gardes et réclame l’avènement, en Belgique, d’une littérature ouverte à la modernité. Deux autres revues serviront pour promouvoir cette politique littéraire : d’abord, en 1884, la jeune équipe tente de coloniser Le Magasin littéraire et artistique, ensuite, en 1894, 3 ans après la fondation de la Jeune Droite et un an après la proclamation de l’encyclique Rerum Novarum, nos 3 hommes fondent la revue Durandal qui paraîtra pendant 20 ans (jusqu’en 1914). Comme nous le verrons, le nom même de la revue fera date dans l’histoire du “mouvement éthique” (appellons-le ainsi...). Parmi les animateurs de cette nouvelle publication, citons, outre Henry Carton de Wiart lui-même, Pol Demade, médecin spécialisé en médecine sociale, et l’Abbé Henri Moeller (1852-1918). Ils seront vite rejoints par une solide équipe de talents : Firmin Van den Bosch, Pierre Nothomb (stagiaire auprès du cabinet d’avocat de Carton de Wiart), Victor Kinon (1873-1953), Maurice Dullaert, Georges Virrès (1869-1946), Arnold Goffin (1863-1934), Franz Ansel (1874-1937), Thomas Braun (1876-1961) et Adolphe Hardy (1868-1954).

Spiritualité et justice sociale

Leur but est de créer un “art pour Dieu” et leurs sources d’inspiration sont les auteurs et les artistes s’inspirant du “symbolisme wagnérien”, à l’instar des Français Léon Bloy, Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, Francis Jammes et Joris Karl Huysmans. Pour cette équipe, comme aussi pour Bloy, les catholiques sont une “minorité souffrante”, surtout en France à l’époque où sont édictées et appliquées les lois du “petit Père Combes”. Autres références françaises : les œuvres d’Ernest Psichari et de Paul Claudel. Le wagnérisme et le catholicisme doivent, en fusionnant dans les œuvres, générer une spiritualité offensive qui s’opposera au “matérialisme bourgeois” (dont celui de Woeste). La spiritualité et l’idée de justice sociale doivent donc marcher de concert. Le contexte belge est toutefois différent de celui de la France : les catholiques belges avaient gagné la bataille métapolitique, ils avaient engrangé une victoire électorale en 1884, à l’époque où Firmin Van den Bosch tentait de noyauter Le Magasin littéraire et artistique. Dans la guerre scolaire, les catholiques enregistrent également des victoires partielles : face aux libéraux, aux libéraux de gauche (alliés implicites des socialistes) et aux socialistes, il s’agit, pour la jeune équipe autour de Carton de Wiart et pour la rédaction de Durandal, de « gagner la bataille de la modernité ». À l’avant-garde socialiste (prestigieuse avec un architecte “Art Nouveau” comme Horta), il faut opposer une avant-garde catholique. La modernité ne doit pas être un apanage exclusif des libéraux et des socialistes. La différence entre ces catholiques qui se veulent modernistes (sûrement avec l’appui du Cardinal) et leurs homologues laïques, c’est qu’ils soutiennent la politique coloniale lancée par Léopold II en Afrique centrale. Le Congo est une terre de mission, une aire géographique où l’héroïsme pionnier ou missionnaire pourra donner le meilleur de lui-même.

Quelles valeurs va dès lors défendre Durandal ? Elle va essentiellement défendre ce que ses rédacteurs nommeront le “sentiment patrial”, présent au sein du peuple, toutes classes confondues. On retrouve cette idée dans le principal roman d’Henry Carton de Wiart, La Cité ardente, œuvre épique consacrée à la ville de Liège. La notion de “sentiment patrial”, nous la retrouvons surtout dans les textes annonciateurs de la “révolution conservatrice” dus à la plume de Hugo von Hofmannsthal, où l’écrivain allemand déplore la disparition des “liens” humains sous les assauts de la modernité et du libéralisme, qui brisent les communautés, forcent à l’exode rural, laissent l’individu totalement esseulé dans les nouveaux quartiers et faubourgs des grandes villes industrielles et engendrent des réflexes individualistes délétères dans la société, où les plaisirs hédonistes, furtifs ou constants selon la fortune matérielle, tiennent lieu d’Ersätze à la spiritualité et à la charité. Cette déchéance sociale appelle une “restauration créatrice”. Le sentiment d’Hofmannsthal sera partagé, mutatis mutandis, par des hommes comme Arthur Moeller van den Bruck et Max Hildebert Boehm.

L’idée “patriale” s’inscrit dans le projet du Chanoine Halflants, issu d’une famille tirlemontoise qui avait assuré le recrutement en Hesbaye de nombreux zouaves pontificaux, pour la guerre entre les États du Pape et l’Italie unitaire en gestation sous l’impulsion de Garibaldi. Avant 1910, le Chanoine Halflants préconisera tolérance et ouverture aux innovations littéraires. Après 1918, il prendra des positions plus “réactionnaires”, plus en phase avec la “bien-pensance” de l’époque et plus liées à l’idéal classique. Qu’est ce que cela veut dire ? Que le Chanoine entendait, dans un premier temps, faire figurer les œuvres littéraires modernes dans les anthologies scolaires, ainsi que la littérature belge (catholique qui adoptait de nouveaux canons stylistiques et des thématiques romanesques profanes). Il s’opposait dans ce combat aux Jésuites, qui n’entendaient faire étudier que des auteurs grecs et latins antiques. Halflants gagnera son combat : les Jésuites finiront par accepter l’introduction de nouveaux écrivains dans les curricula scolaires. De ces efforts naîtra une “anthologie des auteurs belges”. L’objectif, une fois de plus, est de ne pas abandonner les formes modernes d’art et de littérature aux forces libérales et socialistes qui, en épousant les formes multiples d’ “Art Nouveau” apparaissaient comme les pionniers d’une culture nouvelle et libératrice.

Bourgeoisie ethétisante et prêtres maurrassiens

Cette agitation de la Jeune Droite et de Durandal repose, mutatis mutandis, sur un clivage bien net, opposant une bourgeoisie industrielle et matérialiste à une bourgeoisie cultivée et esthétique, qui a le sens du Bien et du Beau que transmettent bien évidemment les humanités gréco-latines. La bourgeoisie matérialiste et industrielle est incarnée non seulement par les libéraux sans principes éthiques solides mais aussi par des catholiques qui se laissent séduire par cet esprit mercantile, contraire au “sentiment patrial”. Cette idée d’un clivage entre matérialistes et esthètes, on la retrouve déjà dans l’œuvre laïque et irreligieuse de Camille Lemonnier (édité en Allemagne, dans des éditions superbes, par Eugen Diederichs). La bourgeoisie affairiste provoque une décadence des mœurs que l’esthétisme de ceux de ses enfants, qui sont pieux et contestataires, doit endiguer. Pour enrayer les progrès de la décadence, il faut, selon les directives données antérieurement par Louis de Bonald en France, lutter contre le libéralisme politique.

C’est à partir du moment où certains jeunes catholiques belges, soucieux des questions sociales, entendent suivre les injonctions de Bonald, que la Jeune Droite et Durandal vont s’inspirer de Charles Maurras, en lui empruntant son vocabulaire combatif et opérant. Les catholiques belges de la Jeune Droite et les Français de l’Action française s’opposent donc de concert au libéralisme politique, en le fustigeant allègrement. Dans ce contexte émerge le phénomène des “prêtres maurrassiens”, avec, à Liège, Louis Humblet (1874-1949), à Mons, Valère Honnay (1883-1949) et, à Bruxelles, Ch. De Smet (1833-1911) et J. Deharveng (1867-1929). Ce maurrasisme est seulement stylistique dans une Belgique assez germanophile avant 1914. Les visions géopolitiques et anti-allemandes du filon maurrassien ne s’imposeront en Belgique qu’à partir de 1914. D’autres auteurs français influencent l’idéologie de Durandal, les 4 “B” : Barrès, Bourget, Bordeaux et Bazin.

C’est Bourget qui exerce l’influence la plus importante : il veut, en des termes finalement très peu révolutionnaires, une “humanité non dégradée”, reposant sur la famille, l’honneur conjugal et les fortes convictions (religieuses). Le poids de Bourget sera de longue durée : on verra que cette éthique très pieuse et très conventionnelle influencera le groupe de la “Capelle-aux-Champs” que fréquentera Hergé, le créateur de Tintin, et Franz Weyergans, le père de François Weyergans (qui répondra par un livre aux idéaux paternels, inspirés de Paul Bourget, livre qui lui a valu le “Grand Prix de la langue française” en 1997, ce qui l’amena plus tard à occuper un siège à l’Académie Française ; cf. : Franz et François, Grasset, 1997 ; pour comprendre l’apport de Bourget, tout à la fois à la modernisation du sentiment littéraire des catholiques et à la critique des œuvres contemporaines de Baudelaire, Stendhal, Taine, Renan et Flaubert, lire : Paul Bourget, Essais de psychologie contemporaine, Plon, Paris, 1937).

La Première Guerre mondiale va bouleverser la scène politique et métapolitique d’une Belgique qui, de germanophile, virera à la francophilie, surtout dans les milieux catholiques. La Grande Guerre génère d’abord une littérature inspirée par les souffrances des soldats. Parmi les morts au combat : le jeune Louis Boumal, lecteur puis collaborateur belge de L’Action française. Autour de ce personnage se créera le “mythe de la jeunesse pure sacrifiée”, que Léon Degrelle, plus tard, reprendra à son compte. Mais c’est surtout son camarade de combat Lucien Christophe (1891-1975), qui a perdu son frère Léon pendant la guerre, qui défendra et illustrera la mémoire de Louis Boumal. Celui-ci, tout comme Christophe, était un disciple d’Ernest Psichari, chantre catholique de l’héroïsme et du dévouement guerriers. Les anciens combattants de l’Yser, Christophe en tête, déploreront l’ingratitude du pays à partir de 1918, l’absence de solidarité nationale une fois les hostilités terminées. Christophe et les autres combattants estiment dès lors que les journalistes et les écrivains doivent s’engager dans la Cité. Un écrivain ne peut pas rester dans sa tour d’ivoire. C’est ainsi que les anciens combattants rejettent l’idée d’un art pour l’art et ajoutent à l’idée d’un art pour Dieu, présent dans les rangs de la Jeune Droite avant 1914, celle d’un art social. Le catholicisme militant, social dans le sillage de Daens et de Rerum Novarum, national au nom du sacrifice de Louis Boumal et Léon Christophe, réclame, à l’instar d’autres idéologies, d’autres milieux sociaux ou habitus politiques, l’engagement.

ACJB et Cercle Rerum novarum

Lucien Christophe va donner l’éveil à une génération nouvelle, qui comptera de jeunes plumes dans ses rangs : Luc Hommel (1896-1960), Carlo de Mey (1895-1962), Camille Melloy (de son vrai nom Camille De Paepe, 1891-1941) et Léopold Levaux (1892-1956). C’est au départ de ce groupe, inspiré par Christophe plutôt que par Carton de Wiart, que se forme l’ACJB (Association Catholique de la Jeunesse Belge). Pierre Nothomb, qui entend préserver l’unité du bloc catholique, œuvrera pour que le groupe rassemblé au sein de la revue Durandal fusionne avec l’ACJB. Quant à la Jeune Droite de Carton de Wiart, avec ses aspirations à la justice sociale, elle fusionnera avec le Cercle Rerum Novarum, animé, entre autres personnalités, par Pierre Daye, futur sénateur rexiste en 1936. Daye a des liens avec les Français Marc Sangnier et l’Abbé Lugan, fondateurs d’une Action Catholique, hostile à l’Action française de Maurras et Pujo.

Le Cercle Rerum Novarum poursuivait les mêmes objectifs que ceux de la Jeune Droite de Carton de Wiart, dans la mesure où il s’opposait à toute politique économique libérale outrancière, comme celle d’un Charles Woeste pourtant ponte du parti catholique, entendait ensuite remobiliser les idéaux de l’Abbé Daens. Il n’était pas sur la même longueur d’onde que l’Action française, plus nationaliste que catholique et plus préoccupée de justifier la guerre contre l’Allemagne (même celle de la république laïcarde) que de réaliser en France, et pour les Français, des idéaux de justice sociale. En Belgique, nous constatons donc, avec C. Vanderpelen-Diagre, que les idéaux nationaux (surtout incarnés par Pierre Nothomb) sont intimement liés aux idéaux de justice sociale et que cette fusion demeurera intacte dans toutes les expressions du catholicisme idéologique belge jusqu’en 1945 (même dans des factions hostiles les unes aux autres, surtout après l’émergence du rexisme).

En 1918, Pierre Nothomb et Gaston Barbanson plaident tous deux pour une “Grande Belgique”, en préconisant l’annexion du Grand-Duché du Luxembourg, du Limbourg néerlandais et de la Flandre zélandaise. Ils prennent des positions radicalement anti-allemandes, rompant ainsi définitivement avec la traditionnelle germanophilie belge du XIXe siècle. Ces positions les rapprochent de l’Action française de Maurras et du maurrassisme implicite du Cardinal Mercier, hostile à l’Allemagne prussianisée et protestante comme il est hostile à l’éthique kantienne, pour lui trop subjectiviste, et, par voie de conséquence, hostile au mouvement flamand et à la flamandisation de l’enseignement supérieur, car ce serait là offrir un véhicule à la germanisation rampante de toute la Belgique, provinces romanes comprises.

Les annexionnistes sont en faveur d’une alliance militaire franco-belge, qui sera fait acquis dès 1920 mais que contesteront rapidement et l’aile gauche du parti socialiste et le mouvement flamand (cf. Dr. Guido Provoost, Vlaanderen en het militair-politiek beleid in België tussen de twee wereldoorlogen – Het Frans-Belgisch militair akkoord van 1920, Davidsfonds, Leuven, 1977). En adoptant cette démarche, les adeptes de la “Grande Belgique” quittent l’orbite du “démocratisme chrétien” qui avait été le leur et celui de leurs amis pour fonder une association nationaliste, le Comité de Politique Nationale (CPN), où se retrouvent Pierre Daye (qui n’est plus alors à proprement parler un “rerum-novarumiste” ou un “daensiste”), l’historien Jacques Pirenne (qui renie ses dettes intellectuelles à l’historiographie allemande), Léon Hennebicq, le leader socialiste et interventionniste Jules Destrée, ami des interventionnistes italiens regroupés autour de Mussolini et d’Annunzio, et un autre socialiste, Louis Piérard.

Les annexionnistes germanophobes et hostiles aux Pays-Bas réclament une occupation de l’Allemagne, son morcellement à l’instar de ce que venait de subir la grande masse territoriale de l’Empire austro-hongrois défunt ou l’Empire ottoman au Levant. Ils réclament également l’autonomisation de la Rhénanie et le renforcement de ses liens économiques (qui ont toujours été forts) avec la Belgique. Enfin, ils veulent récupérer le Limbourg devenu officiellement néerlandais en 1839 et la Flandre zélandaise afin de contrôler tout le cours de l’Escaut en aval d’Anvers. Ils veulent les cantons d’Eupen-Malmédy (qu’ils obtiendront) mais aussi 8 autres cantons rhénans qui resteront allemands. Le Roi Albert Ier refuse cette politique pour ne pas se mettre définitivement les Pays-Bas et le Luxembourg à dos et pour ne pas créer l’irréparable avec l’Allemagne. Les annexionnistes du CPN se trouveront ainsi en porte-à-faux par rapport à la personne royale, que leur option autoritariste cherchait à valoriser.

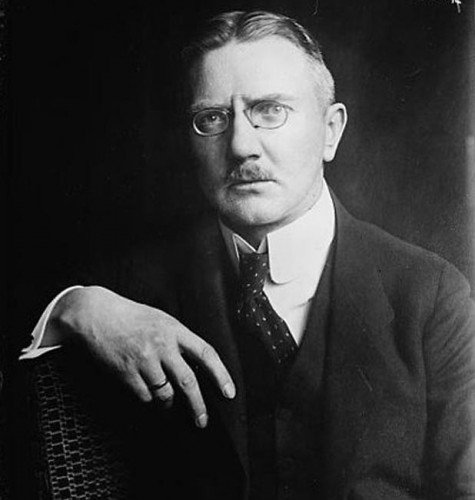

Le ressourcement italien de Pierre Nothomb

Le passage du démocratisme de la Jeune Droite au nationalisme du CPN s’accompagne d’un véritable engouement pour l’œuvre de Maurice Barrès. Plus tard, quand l’Action française, et, partant, toutes les formes de nationalisme français hostiles aux anciens empires d’Europe centrale, se retrouvera dans le collimateur du Vatican, le nouveau nationalisme belge de Nothomb et la frange du parti socialiste regroupée autour de Jules Destrée va plaider pour un “ressourcement italien”, suite au succès de la Marche sur Rome de Mussolini, que Destrée avait rencontré en Italie quand il allait, là-bas, soutenir les efforts des interventionnistes italiens avant 1915. Nothomb [ci-contre] traduira ce nouvel engouement italophile, post-barrèsien et post-maurrassien, en un roman, Le Lion ailé, paru en 1926, la même année où la condamnation de l’Action française est proclamée à Rome. Le Lion ailé, écrit C. Vanderpelen-Diagre, est une ode à la nouvelle Italie fasciste. Celle-ci est posée comme un modèle à imiter : il faut, pense Nothomb, favoriser une “contagion romaine”, ce qui conduira inévitablement à un “rajeunissement national”, par l’émergence d’un “ordre vivant”. Jules Destrée, le leader socialiste séduit par l’Italie, celle de l’interventionnisme et celle de Mussolini, salue la parution de ce roman et en encourage la lecture. La réception d’éléments idéologiques fascistes n’est donc pas le propre d’une droite catholique et nationale : elle a animé également le pilier socialiste dans le chef d’un de ses animateurs les plus emblématiques.

Le passage du démocratisme de la Jeune Droite au nationalisme du CPN s’accompagne d’un véritable engouement pour l’œuvre de Maurice Barrès. Plus tard, quand l’Action française, et, partant, toutes les formes de nationalisme français hostiles aux anciens empires d’Europe centrale, se retrouvera dans le collimateur du Vatican, le nouveau nationalisme belge de Nothomb et la frange du parti socialiste regroupée autour de Jules Destrée va plaider pour un “ressourcement italien”, suite au succès de la Marche sur Rome de Mussolini, que Destrée avait rencontré en Italie quand il allait, là-bas, soutenir les efforts des interventionnistes italiens avant 1915. Nothomb [ci-contre] traduira ce nouvel engouement italophile, post-barrèsien et post-maurrassien, en un roman, Le Lion ailé, paru en 1926, la même année où la condamnation de l’Action française est proclamée à Rome. Le Lion ailé, écrit C. Vanderpelen-Diagre, est une ode à la nouvelle Italie fasciste. Celle-ci est posée comme un modèle à imiter : il faut, pense Nothomb, favoriser une “contagion romaine”, ce qui conduira inévitablement à un “rajeunissement national”, par l’émergence d’un “ordre vivant”. Jules Destrée, le leader socialiste séduit par l’Italie, celle de l’interventionnisme et celle de Mussolini, salue la parution de ce roman et en encourage la lecture. La réception d’éléments idéologiques fascistes n’est donc pas le propre d’une droite catholique et nationale : elle a animé également le pilier socialiste dans le chef d’un de ses animateurs les plus emblématiques.

Nothomb avait créé, comme pendant à son CPN, les Jeunesses nationales en 1924. Ce mouvement appelle à un renforcement de l’exécutif, à une organisation corporative de l’État, à l’émergence d’un racisme défensif et d’un anti-maçonnisme, tout en prônant un catholicisme intransigeant (ce qui n’était pas du tout le cas dans l’Italie de l’époque, les Accords du Latran n’ayant pas encore été signés). Le CPN et les Jeunesses nationales entendant, de concert, poser un “compromis entre la raison et l’aventure”. Ce message apparaît trop pauvre pour d’autres groupes en gestation, dont la Jeunesse nouvelle et le groupe royaliste Pour l’autorité. Ces 2 groupes, fidèles en ce sens à la volonté du Roi, refusent le programme de politique étrangère du CPN et des Jeunesses nationales : ils veulent maintenir des rapports normaux avec les Pays-Bas, le Luxembourg et l’Allemagne. Ils insistent aussi sur la nécessité d’imposer une “direction de l’âme et de l’esprit”. En réclamant une telle “direction”, ils enclenchent ce que l’on pourrait appeler, en un langage gramscien, une “bataille métapolitique”, qu’ils qualifiaient, en reprenant certaines paroles du Cardinal Mercier, d’“apostolat par la plume”. Ils s’alignent ainsi sur la volonté de Pie XI de promouvoir un “catholicisme plus intransigeant”, en dépit de l’hostilité du Pontife romain à l’endroit de la francophilie maurrassienne du Primat de Belgique. Enfin, les 2 nouveaux groupes sur l’échiquier politico-métapolitique belge entendent suivre les injonctions de l’encyclique Quas Primas de 1925, proclamant la « royauté du Christ », du « Christus Rex », induisant ainsi le vocable “Rex” dans le vocabulaire politique du pilier catholique, ce qui conduira, après de nombreux avatars, à l’émergence du mouvement rexiste de Léon Degrelle, quand celui-ci rompra les ponts avec ses anciens associés du parti catholique. Le « catholicisme plus intransigeant », réclamé par Pie XI, doit s’imposer aux sociétés par des moyens modernes, par des technologies de communication comme la “TSF” et l’édition de masse (ce à quoi s’emploiera Degrelle, sur ordre de la hiérarchie catholique la plus officielle, au début des années 30).

Beauté, intelligence, moralité

L’appareil de cette offensive métapolitique s’est mis en place, par la volonté du Cardinal Mercier, au moins dès 1921. Celui-ci préside à la fondation de La Revue catholique des idées et des faits (RCIF), revue plus philosophique que théologique, Mercier n’étant pas théologien mais philosophe. Le Cardinal confie la direction de cette publication à l’Abbé René-Gabriel Van den Hout (1886-1969), professeur à l’Institut Saint Louis de Bruxelles et animateur du futur quotidien La Libre Belgique dans la clandestinité pendant la Première Guerre mondiale. L’Abbé Van den Hout avait également servi d’intermédiaire entre Mercier et Maurras. Volontairement le Primat de Belgique et l’Abbé Van den Hout vont user d’un ton et d’une verve polémiques pour fustiger les adversaires de ce renouveau à la fois catholique et national (ton que Degrelle et son caricaturiste Jam pousseront plus tard jusqu’au paroxysme). En 1924, avant la condamnation de Maurras et de l’Action française par le Vatican, les Abbés Van den Hout et Norbert Wallez, flanqués du franciscain Omer Englebert, envisagent de fonder une Action belge (AB), pendant de ses homologues française et espagnole (sur l’Accion Española, cf. Raùl Morodo, Los origenes ideologicos del franquismo : Accion Española, Alianza Editorial, Madrid, 1985). On a pu parler ainsi du “maurrassisme des trois abbés”. Le programme intellectuel de la RCIF et de l’AB (qui restera finalement en jachère) est de lutter contre les formes de romantisme, mouvement littéraire accusé de véhiculer un “subjectivisme relativiste” (donc un individualisme), ou, comme le décrira Carl Schmitt en Allemagne, un “occasionalisme”. Les abbés et leurs journalistes plaideront pour le classicisme, reposant, lui, à leurs yeux, sur 3 critères : la beauté, l’intelligence et la moralité (le livre de référence pour ce “classicisme” demeure celui d’Adrien de Meeüs, Le coup de force de 1660, Nouvelle Société d’Édition, Bruxelles, 1935 ; à ce propos, voir plus bas notre article « Années 20 et 30 : la droite de l’établissement francophone en Belgique, la littérature flamande et le ‘nationalisme de complémentarité’ »).

Revenons maintenant à l’ACJB. En 1921 également, les abbés Brohée et Picard (celui-là même qui mettra Degrelle en selle 10 ans plus tard) entament, eux aussi, un combat métapolitique. Leur objectif ? “Guider les lectures” par le truchement d’un organe intitulé Revue des auteurs et des livres. Au départ, cet organe se veut avant-gardiste mais proposera finalement des lectures figées, déduites d’une littérature bien-pensante. L’ACJB a donc des objectifs culturels et non pas politiques. C’est cette option métapolitique qui provoque une rupture qui se concrétise par la fondation de la Jeunesse nouvelle, parallèle à l’éparpillement de l’équipe de Durandal, dont les membres ont tous été appelés à de hautes fonctions administratives ou politiques. La Jeunesse nouvelle se donne pour but de “régénérer la Cité”, en y introduisant des ferments d’ordre et d’autorité. Elle vise l’instauration d’une monarchie antiparlementaire et nationaliste. Elle réagit à l’instauration du “suffrage universel pur et simple”, imposé par les socialistes, car celui-ci exprimerait la “déchéance morale et politique” d’une société (sa fragmentation et son émiettement en autant de petites républiques individuelles – la “verkaveling” dit-on en néerlandais ; cf. l’ouvrage humoristique mais intellectuellement fort bien charpenté de Rik Vanwalleghem, België Absurdistan – Op zoek naar de bizarre kant van België, Lannoo, Tielt, 2006, livre qui met en exergue l’effet final et contemporain de l’individualisme et de la disparition de toute éthique). La Jeunesse nouvelle s’oppose aussi au nouveau système belge né des “accords de Lophem” de 1919 où les acteurs sociaux et les partis étaient convenus d’un “deal”, que l’on entendait pérenniser jusqu’à la fin des temps en excluant systématiquement tout challengeur survenu sur la piste par le biais d’élections. Ce “deal” repose sur un canevas politique donné une fois pour toutes, posé comme définitif et indépassable, avec des forces seules autorisées à agir sur l’échiquier politico-parlementaire.

L’organe de la Jeunesse nouvelle, soit La Revue de littérature et d’action devient La Revue d’action dès que l’option purement métapolitique cède à un désir de s’immiscer dans le fonctionnement de la Cité. La revue d’Action devient ainsi, de 1924 à 1934, la porte-paroles du mouvement Pour l’autorité, dont la cheville ouvrière sera un jeune historien en vue de la matière de Bourgogne, Luc Hommel. Pour celui-ci, la revue est un “laboratoire d’idées” visant une réforme de l’État, qui reposera sur un renforcement de l’exécutif, sur le corporatisme et le nationalisme (à références “bourguignonnes”) et sur le suffrage familial, appelé à corriger les effets jugés pervers du “suffrage universel pur et simple”, imposé par les socialistes dès le lendemain de la Première Guerre mondiale. Hommel et ses amis préconisent de rester au sein du Parti Catholique, d’y être un foyer jeune et rénovateur. Les adeptes des thèses de la La Revue d’action ne rejoindront pas Rex. Parmi eux : Etienne de la Vallée-Poussin (qui dirigera un moment Le Vingtième siècle fondé par l’Abbé Wallez), Daniel Ryelandt (qui témoignera contre Léon Degrelle dans le fameux film que lui consacrera Charlier et qui était destiné à l’ORTF mais qui ne passera pas sur antenne après pression diplomatique belge sur les autorités de tutelle françaises), Gaëtan Furquim d’Almeida, Charles d’Aspremont-Lynden, Paul Struye, Charles du Bus de Warnaffe. La revue et le groupe Pour l’autorité cesseront d’exister en 1935, quand Hommel deviendra chef de cabinet de Paul van Zeeland. Plusieurs protagonistes de Pour l’autorité œuvreront ensuite au Centre d’Études pour la Réforme de l’État (CERE), dont Hommel, de la Vallée-Poussin et Ryelandt. Ils s’opposeront farouchement Rex en dépit d’une volonté commune de renforcer l’exécutif autour de la personne du Roi. L’idéal d’un renforcement de l’exécutif est donc partagé entre adeptes et adversaires de Rex.

La “Troisième voie” de Raymond De Becker

La période qui va de 1927 à 1939 est aussi celle d’une recherche fébrile de la “troisième voie”. C’est dans ce contexte qu’émergera une figure que l’on commence seulement à redécouvrir en Belgique, en ce début de deuxième décennie du XXIe siècle : Raymond De Becker. Contrairement à tous les mouvements que nous venons de citer, qui veulent demeurer au sein du pilier catholique, les hommes partis en quête d’une “troisième voie” cherchent à élargir l’horizon de leur engagement à toutes les forces sociales agissant dans la société. Ils ont pour point commun de rejeter le libéralisme (assimilé au “vieux monde”) et entendent valoriser toutes les doctrines exigeant une adhésion qu’ils apparentent à la foi : le catholicisme, le communisme, le fascisme, considérés comme seules forces d’avenir. C’est la démarche de ceux que Jean-Louis Loubet del Bayle nommera, dans son ouvrage de référence, les “non-conformistes des années 30”. Loubet del Bayle n’aborde que le paysage intellectuel français de l’époque. Qu’en est-il en Belgique ? Le cocktail que constituera la “troisième voie” ardemment espérée contiendra, francophonie oblige, bon nombre d’ingrédients français : Blondel (vu ses relations et son influence sur le Cardinal Mercier, sans oublier sa “doctrine de l’action”), Archambault, Mounier (le personnalisme), Gabriel Marcel (la distinction entre l’Être et l’Avoir), Maritain et Daniel-Rops. Après la condamnation de Maurras et de l’Action française par le Vatican, Jacques Maritain, que Paul Sérant classe comme un “dissident de l’Action française”, remplace, dès 1926, Maurras comme gourou de la jeunesse catholique et autoritaire en Belgique. R. de Becker et Henry Bauchau (toujours actif aujourd’hui, et qui nous livre un regard sur cette époque dans son tout récent récit autobiographique, L’enfant rieur, Actes Sud, 2011 ; R. De Becker y apparaît sous le prénom de “Raymond” ; voir surtout les pp. 157 à 166) sont les 2 hommes qui entretiendront une correspondance avec Maritain et participeront aux rencontres de Meudon. Du “nationalisme intégral de Maurras”, que voulait importer Nothomb, on passe à l’“humanisme intégral” de Maritain.

La période qui va de 1927 à 1939 est aussi celle d’une recherche fébrile de la “troisième voie”. C’est dans ce contexte qu’émergera une figure que l’on commence seulement à redécouvrir en Belgique, en ce début de deuxième décennie du XXIe siècle : Raymond De Becker. Contrairement à tous les mouvements que nous venons de citer, qui veulent demeurer au sein du pilier catholique, les hommes partis en quête d’une “troisième voie” cherchent à élargir l’horizon de leur engagement à toutes les forces sociales agissant dans la société. Ils ont pour point commun de rejeter le libéralisme (assimilé au “vieux monde”) et entendent valoriser toutes les doctrines exigeant une adhésion qu’ils apparentent à la foi : le catholicisme, le communisme, le fascisme, considérés comme seules forces d’avenir. C’est la démarche de ceux que Jean-Louis Loubet del Bayle nommera, dans son ouvrage de référence, les “non-conformistes des années 30”. Loubet del Bayle n’aborde que le paysage intellectuel français de l’époque. Qu’en est-il en Belgique ? Le cocktail que constituera la “troisième voie” ardemment espérée contiendra, francophonie oblige, bon nombre d’ingrédients français : Blondel (vu ses relations et son influence sur le Cardinal Mercier, sans oublier sa “doctrine de l’action”), Archambault, Mounier (le personnalisme), Gabriel Marcel (la distinction entre l’Être et l’Avoir), Maritain et Daniel-Rops. Après la condamnation de Maurras et de l’Action française par le Vatican, Jacques Maritain, que Paul Sérant classe comme un “dissident de l’Action française”, remplace, dès 1926, Maurras comme gourou de la jeunesse catholique et autoritaire en Belgique. R. de Becker et Henry Bauchau (toujours actif aujourd’hui, et qui nous livre un regard sur cette époque dans son tout récent récit autobiographique, L’enfant rieur, Actes Sud, 2011 ; R. De Becker y apparaît sous le prénom de “Raymond” ; voir surtout les pp. 157 à 166) sont les 2 hommes qui entretiendront une correspondance avec Maritain et participeront aux rencontres de Meudon. Du “nationalisme intégral de Maurras”, que voulait importer Nothomb, on passe à l’“humanisme intégral” de Maritain.

Le passage du maurrassisme au maritainisme implique une acceptation de la démocratie et de ses modes de fonctionnement, ainsi que du pluralisme qui en découle, et constate l’impossibilité de retrouver le pouvoir supratemporel du Saint Empire (vu de France, on peut effectivement affirmer que le Saint Empire, assassiné par Napoléon, ou l’Empire austro-hongrois, assassiné par Poincaré et Clemenceau, est une “forme morte” ; ailleurs, notamment en Autriche et en Hongrie, c’est moins évident... Il suffit d’évoquer les propositions très récentes du ministre hongrois Orban pour “resacraliser” l’État, notamment en le dépouillant du label de “république”). Par voie de conséquence, les maritainistes ne réclameront pas l’avènement d’une “Cité chrétienne”. En ce sens, ils vont plus loin que le Chanoine Jacques Leclercq (cf. infra) en Belgique, dont le souci, tout au long de son itinéraire, sera de maintenir une dose de divin et, subrepticement, un certain contrôle clérical sur la Cité, même aux temps d’après-guerre où le maritainisme débouchera partiellement sur la création et l’animation d’un parti politique “catho-communisant”, l’UDB (auquel adhèrera un William Ugeux, ancien journaliste au Vingtième Siècle et responsable de la “Sûreté de l’État” pour le compte du gouvernement Pierlot revenu de son exil londonien).

La Cité, rêvée par les adeptes d’une “troisième voie” d’inspiration maritainiste, est un “contrat entre fidèles et infidèles”, visant l’unité de la Cité, une unité minimale, certes, mais animée par l’amitié et la fraternité entre les hommes. Cette vision repose évidemment sur la définition “ouverte” que Maritain donne de l’humanisme. D’où la question que lui poseront finalement R. de Becker et Léon Degrelle : “Où sont les points d’appui ?”. En effet, l’idée d’une “humanité ouverte” ne permet pas de construire une Cité, qui, toujours, par la force des choses, aura des limites et/ou des frontières. Le maritainisme ne fera pas l’unité des anciens maurrassiens, des chercheurs de “troisièmes voies” voire des thomistes recyclés, modernisant leur discours, ou des “demanistes” socialistes non hostiles à la religion : le monde catholique se divisera en chapelles antagonistes qui le conduiront à l’implosion, à une sorte de guerre civile entre catholiques (surtout à partir de l’émergence de Rex) et à une sorte d’aggiornamento technocratique (qui, parti du technocratisme à l’américaine de Van Zeeland, donnera à terme la “plomberie” de Dehaene et son basculement dans les fiascos financiers postérieurs à l’automne 2008) ou à un discours assez hystérique et filandreux, évoquant justement le thème de l’humanisme maritainien, avec Joëlle Milquet qui abandonne l’appelation de Parti Social-Chrétien pour prendre celle de CdH (Centre Démocrate et Humaniste).

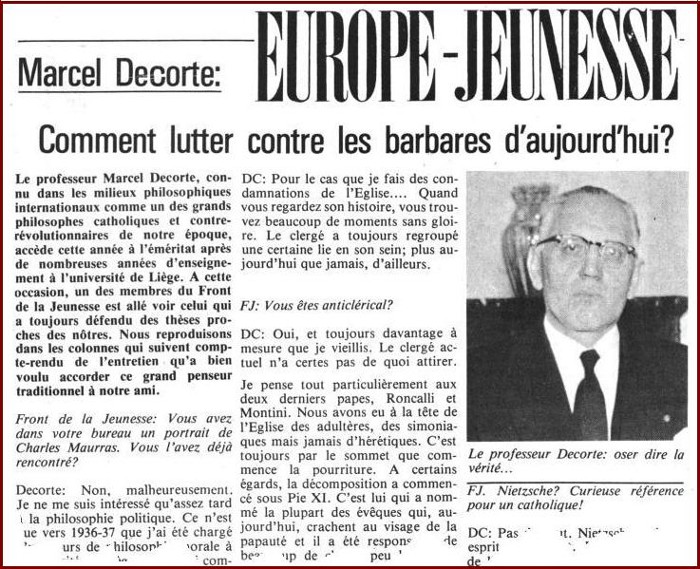

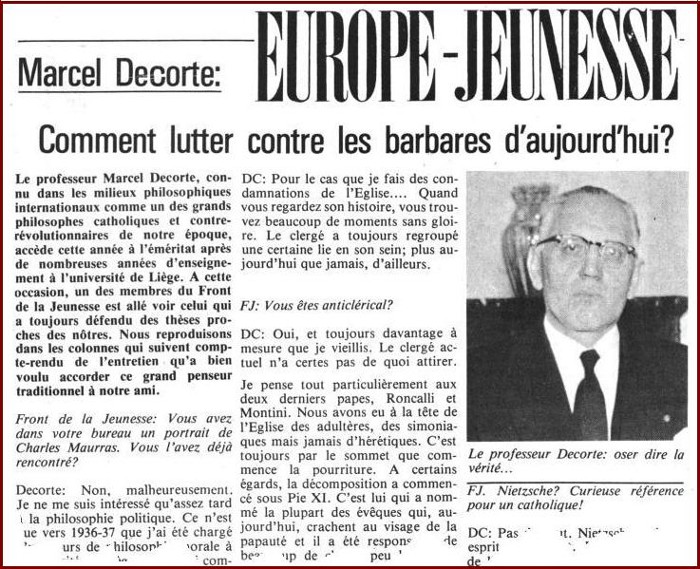

Marcel De Corte

[En septembre 1975, Marcel De Corte accorde une entretien au Front de la jeunesse publié dans la rubrique "Europe-Jeunesse" du Nouvel Europe magazine (NEM)]

[En septembre 1975, Marcel De Corte accorde une entretien au Front de la jeunesse publié dans la rubrique "Europe-Jeunesse" du Nouvel Europe magazine (NEM)]

Quelles seront les expressions de l’humanisme intégral de Maritain en Belgique ? Il y aura notamment la Nouvelle équipe d’Yvan Lenain (1907-1965). Lenain est un philosophe thomiste de formation, qui veut “une Cité régénérée par la spiritualité”. Si, au départ, Lenain s’inscrit dans le sillage de Maritain, les évolutions et les aggiornamenti de ce dernier le contraindront à adopter une position thomiste plus traditionnelle. Par ailleurs, l’ouverture aux gens de gauche, les “infidèles” avec lesquels on aurait pu, le cas échéant, conclure un contrat, s’est avérée un échec. Le repli sur un thomisme plus classique est sans doute dû à l’influence d’une figure aujourd’hui oubliée, Marcel De Corte (1905-1994), professeur de philosophie à l’Université de Liège. De Corte, actif partout, notamment dans une revue peu suspecte de “catholicisme”, comme Hermès de Marc. Eemans et René Baert, est beaucoup plus ancré dans le catholicisme traditionnel (et aristotélo-thomiste) que ne l’était Lenain au départ : il rompra d’ailleurs avec Maritain en 1937, comme beaucoup d’autres auteurs belges, qui ne supportaient pas le soutien que l’humaniste intégral français apportait aux républicains espagnols (en Belgique, l’hostilité, y compris à gauche, à la République espagnole vient du fait que l’ambassadeur de Belgique, qui avait fait des locaux de l’ambassade du royaume un centre de la Croix Rouge, fut abattu par la police madrilène en 1936, laquelle vida ensuite le bâtiment de la légation de tous les réfugiés et éclopés qui s’y trouvaient et massacra les blessés dans la foulée). La pensée de De Corte, consignée dans 2 gros volumes parus dans les années 50, reste d’actualité : la notion de “dissociété”, qu’il a contribué à forger, est reprise aujourd’hui, même à gauche de l’échiquier politique français, notamment par le biais de l’ouvrage de Jacques Généreux, intitulé La dissociété (Seuil, 2006 ; pour se référer à De Corte directement, lire : Marcel De Corte, De la dissociété, éd. Remi Perrin, 2002).

Raymond De Becker : électron libre

Entre toutes les chapelles politico-littéraires de la Belgique francophone des années 30, R. De Becker va jouer le rôle d’intermédiaire, tout en demeurant un “électron libre”, comme le qualifie C. Vanderpelen-Diagre. De Becker, bien que catholique à l’époque (après la guerre, il ne le sera plus, lorsqu’il œuvrera, avec Louis Pauwels, dans le réseau Planète), ne plaide jamais pour une orthodoxie catholique : il incarne en effet un mysticisme très personnel, rétif à tout encadrement clérical. Dans ses efforts, il aura toujours l’appui de Maritain (avant la rupture suite aux événements d’Espagne) et du Chanoine Jacques Leclercq, qui fut d’abord un maritainiste plus ou mois conservateur avant de devenir, via les revues et associations qu’il animait, le fondateur du nouveau démocratisme chrétien, à tentations marxistes, de l’après-1945. De Becker va jouer aussi le rôle du relais entre les “non-conformistes” français et leurs homologues belges. En 1935, il se rend ainsi à la fameuse abbaye de Pontigny en Bourgogne, véritable laboratoire d’idées nouvelles où se rencontraient des hommes d’horizons différents soucieux de dépasser les clivages politiques en place. C’est à l’invitation de Paul Desjardins (2), qui organise en 1935 une rencontre sur le thème de l’ascétisme, que De Becker rencontre à Pontigny Nicolas Berdiaev, André Gide et Martin Buber.

Le reproche d’antisémitisme qu’on lui lancera à la tête, surtout dans le milieu assez abject des “tintinophobes” parisiens, ne tient pas, ne fût-ce qu’au regard de cette rencontre ; par ailleurs, les séminaires de Pontigny doivent être mis en parallèle avec leurs équivalents allemands organisés par le groupe de jeunesse Köngener Bund, auxquelles Buber participait également, aux côtés d’exposants communistes et nationaux-socialistes. En étudiant parallèlement de telles initiatives, on apprendra véritablement ce que fut le “non-conformisme” des années 30, dans le sillage de l’esprit de Locarno (sur l’impact intellectuel de Locarno : lire les 2 volumes publiés par le CNRS sous la direction de Hans Manfred Bock, Reinhart Meyer-Kalkus et Michel Trebitsch, Entre Locarno et Vichy – les relations culturelles franco-allemandes dans les années 30, CNRS éditions, 1993 ; cet ouvrage explore dans le détail les idéaux pacifistes, liés à l’idée européenne et au désir de sauvegarder le patrimoine de la civilisation européenne, dans le sillage d’Aristide Briand, du paneuropéisme à connnotations catholiques, de Friedrich Sieburg, des personnalistes de la revue L’Ordre nouveau, de Jean de Pange, des germanistes allemands Ernst Robert Curtius et Leo Spitzer, de la revue Europe, où officiera un Paul Colin, etc.).

De Becker, toujours soucieux de traduire dans les réalités politiques et culturelles belges les idées d’humanisme intégral de Maritain, accepte le constat de son maître-à-penser français : il n’est plus possible de rétablir l’harmonie du corporatisme médiéval dans les sociétés modernes ; il faut donc de nouvelles solutions et pour les promouvoir dans la société, il faut créer des organes : ce sera , d’une part, la Centrale politique de la jeunesse, présidée par André Mussche, dont le secrétaire sera De Becker, et, d’autre part, la revue L’esprit nouveau, où l’on retrouve l’ami de toujours, celui qui ne trahira jamais De Becker et refusera de le vouer aux gémonies, Henry Bauchau. Les objectifs que se fixent Mussche, De Becker et Bauchau sont simples : il faut traduire dans les faits la teneur des encycliques pontificales, en instaurant dans le pays une économie dirigée, anti-capitaliste, ou plus exactement anti-trust, qui garantira la justice sociale. Toujours dans l’esprit de Maritain, De Becker se fait le chantre d’une “nouvelle culture”, personnaliste, populaire et attrayante pour les non-croyants (comme on disait à l’époque). Il appellera cette culture nouvelle, la “culture communautaire”. Lors du Congrès de Malines de 1936, Bauchau se profile comme le théoricien et la cheville ouvrière de ce mouvement “communautaire” ; il est rédacteur depuis 1934 à La Cité chrétienne du Chanoine Leclercq, qui essaie de réimbriquer le christianisme (et, partant, le catholicisme) dans les soubresauts de la vie politique, animée par les totalitarismes souvent victorieux à l’époque, toujours challengeurs. Cette volonté de “ré-imbriquer” passe par des compromissions (qu’on espère passagères) avec l’esprit du temps (ouverture au socialisme voire au communisme).

“Communauté” et “Capelle-aux-Champs”

En 1937, les “communautaires” maritainiens créent l’École supérieure d’humanisme, établie au n°21 de la Rue des Deux Églises à Bruxelles. Cette école prodigue des cours de “formation de la personnalité”, comprenant des leçons de philosophie, d’esthétique et d’histoire de l’art et de la culture. Le corps académique de cette école est prestigieux : on y retrouve notamment le Professeur De Corte. Cette école dispose également de relais, dont l’auberge “Au Bon Larron” de Pepinghem, où l’Abbé Leclercq reçoit ses étudiants et disciples, le cercle “Communauté” à Louvain chez la mère de De Becker, où se rend régulièrement Louis Carette, le futur Félicien Marceau. Enfin, dernier relais à signaler : le groupe de la “Capelle-aux-Champs”, sous la houlette bienveillante du Père Bonaventure Feuillien et du peintre Evany [Eugène van Nijverseel] (ami d’Hergé). Le créateur de Tintin fréquentera ce groupe, qui est nettement moins politisé que les autres et où l’on ne pratique pas la haute voltige philosophique. Quelles autres figures ont-elles fréquenté le groupe de la “Capelle-aux-Champs” ? La “Capelle-aux-Champs” ou Kapelleveld se situe exactement à l’endroit du campus de Louvain-en-Woluwé et de l’hôpital universitaire Saint Luc. C’était avant guerre un lieu idyllique, comme en témoigne la fresque ornant la station de métro “Vandervelde” qui y donne accès aujourd’hui.

En 1937, les “communautaires” maritainiens créent l’École supérieure d’humanisme, établie au n°21 de la Rue des Deux Églises à Bruxelles. Cette école prodigue des cours de “formation de la personnalité”, comprenant des leçons de philosophie, d’esthétique et d’histoire de l’art et de la culture. Le corps académique de cette école est prestigieux : on y retrouve notamment le Professeur De Corte. Cette école dispose également de relais, dont l’auberge “Au Bon Larron” de Pepinghem, où l’Abbé Leclercq reçoit ses étudiants et disciples, le cercle “Communauté” à Louvain chez la mère de De Becker, où se rend régulièrement Louis Carette, le futur Félicien Marceau. Enfin, dernier relais à signaler : le groupe de la “Capelle-aux-Champs”, sous la houlette bienveillante du Père Bonaventure Feuillien et du peintre Evany [Eugène van Nijverseel] (ami d’Hergé). Le créateur de Tintin fréquentera ce groupe, qui est nettement moins politisé que les autres et où l’on ne pratique pas la haute voltige philosophique. Quelles autres figures ont-elles fréquenté le groupe de la “Capelle-aux-Champs” ? La “Capelle-aux-Champs” ou Kapelleveld se situe exactement à l’endroit du campus de Louvain-en-Woluwé et de l’hôpital universitaire Saint Luc. C’était avant guerre un lieu idyllique, comme en témoigne la fresque ornant la station de métro “Vandervelde” qui y donne accès aujourd’hui.

C’est donc là, au beau milieu de ce sable et de ces bouleaux, que se retrouvaient Marcel Dehaye (qui écrira dans la presse collaborationniste sous le pseudonyme plaisant de “Jean de la Lune”), Jean Libert (qui sera épuré), Franz Weyergans (le père de François Weyergans) et Jacques Biebuyck. L’idéal qui y règne est l’idéal scout (ce qui attire justement Hergé) ; on n’y cause pas politique, on vise simplement à donner à ses contemporains “un cœur simple et bon”. L’initiative a l’appui de Jacques Leclercq. En dépit de ses connotations catholiques, le groupe se reconnaît dans un refus général de l’esprit clérical et bondieusard (voilà sans doute pourquoi Tintin, héros créé par la presse catholique, n’exprime aucune religion dans ses aventures. Comme bon nombre d’avatars du maritainisme, les amis de la “Capelle-aux-Champs” manifestent une volonté d’ouverture sur l’“ailleurs”. Mais leurs recherches implicites ne sont pas tournées vers une réforme en profondeur de la Cité. Les thèmes sont plutôt moraux, au sens de la bienséance de l’époque : on y réfléchit sur le péché, l’adultère, un peu comme dans l’œuvre de François Mauriac, qui avait appelé à jeter « un regard franc sur un monde dénaturé ».

L’esprit de “Capelle-aux-Champs” est également, dans une certaine mesure, un avatar lointain et original de l’impact de Bourget sur la littérature catholique du début du siècle (pour saisir l’esprit de ce groupe, lire entre autres ouvrages : J. Libert, Capelle aux Champs, Les écrits, Bruxelles, 1941 [5°éd.] et Plénitude, Les écrits, 1941 ; J. Biebuyck, Le rire du cœur, Durandal, Bruxelles, [s. d., probablement après guerre] et Le serpent innocent, Casterman, Tournai, 1971 [préf. de F. Weyergans] ; Franz Weyergans, Enfants de ma patience, éd. Universitaires, Paris, 1964 et Raisons de vivre, Les écrits, 1944 ; cet ouvrage est un hommage de F. Weyergans à son propre père, exactement comme son fils François lui dédiera Franz et François en 1997).

Notons enfin que les éditions “Les Écrits” ont également publié de nombreuses traductions de romans scandinaves, finnois et allemands, comme le firent par ailleurs les fameuses éditions de “La Toison d’Or”, elles carrément collaborationnistes pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale, dans le but de dégager l’opinion publique belge de toutes les formes de parisianismes et de l’ouvrir à d’autres mondes. Le traducteur des éditions “Les Écrits” fut-il le même que celui des éditions “La Toison d’Or”, soit l’Israélite estonien Sulev J. Kaja (alias Jacques Baruch, 1919-2002), condamné sévèrement par les tribunaux incultes de l’épuration et sauvé de la misère et de l’oubli par Hergé lors du lancement de l’hebdomadaire Tintin dès 1946 ? Le pays aurait bien besoin de quelques modestes traducteurs performants de la trempe d’un Sulev J. Kaja...) (2).

Revenons aux animateurs du groupe de la Capelle-aux-Champs. Il y a d’abord Marcel Dehaye (1907-1990) qui explore le monde de l’enfance, exalte la pureté et l’innocence et, avec son personnage Bob ou l’enfant nouveau campe un garçonnet « qui ne sera ni banquier ni docteur ni soldat ni député ». Pendant la Deuxième Guerre mondiale, Dehaye collabora au Soir et au Nouveau Journal sous le pseudonyme de “Jean de la Lune”, ce qui le sauvera sans nul doute des griffes de l’épuration : il aurait été en effet du plus haut grotesque de lire une manchette dans la presse signalant que « l’auditorat militaire a condamné Jean de la Lune à X années de prison et à l’indignité nationale ».

Jacques Biebuyck (1909-1993) est issu, lui, d’une famille riche, ruinée en 1929. Il a fait un séjour de 3 mois à la Trappe. Il a d’abord été fonctionnaire au ministère de l’intérieur puis journaliste. C’est un ami de Raymond De Becker. Il professe un anti-intellectualisme et prône de se fier à l’instinct. Pour lui, la jeunesse doit demeurer “vierge de toute corruption politique”. Biebuyck rejette la politique, qui se déploie dans un “monde de malhonnêtes”. Il renoue là avec un certain esprit de l’ACJB à ses débuts, où le souci culturel primait l’engagement proprement politique. L’illustrateur des œuvres de Biebuyck, et d’autres protagonistes de la Capelle-aux-Champs fut Pierre Ickx, ami d’Hergé et spécialisé dans les dessins de scouts idéalisés.

Jean Libert (1913-1981), lui, provient d’une famille qui s’était éloignée de la religion, parce qu’elle estimait que celle-ci avait basculé dans le “mercantilisme”. À 16 ans, Libert découvre le mouvement scout (comme Hergé auparavant). Ses options spirituelles partent d’une volonté de suivre les enseignements de Saint François d’Assise, comme le préconisait aussi le Père Bonaventure Feuillien. “Nono”, le héros de J. Libert dans son livre justement intitulé Capelle-aux-Champs (cf. supra), va incarner cette volonté. Il s’agit, pour l’auteur et son héros, de conduire l’homme vers une vie joyeuse et digne, héroïque et féconde. Libert se fait le chantre de l’innocence, de la spontanéité, de la pureté (des sentiments) et de l’instinct.

Jean Libert et la “mystique belge”

En 1938, avec Antoine Allard, Jean Libert opte pour l’attitude pacifiste et neutraliste, induite par le rejet des accords militaires franco-belges et la déclaration subséquente de neutralité qu’avait proclamée le Roi Léopold III en octobre 1936, tout en arguant qu’une conflagration qui embraserait toute l’Europe entraînerait le déclin irrémédiable du Vieux Continent (cf. les idées pacifistes de Maurice Blondel, à la fin de sa vie, consignée dans son ouvrage, Lutte pour la civilisation et philosopohie de la paix, Flammarion, 1939 ; cet ouvrage est rédigé dans le même esprit que le “manifeste neutraliste” et inspire, fort probablement, le discours royal aux belligérants dès septembre 1939). J. Libert signe donc ce fameux manifeste neutraliste des intellectuels, notamment patronné par Robert Poulet.

Parallèlement à cet engagement neutraliste, dépourvu de toute ambigüité, Libert plaide pour l’éclosion d’une “mystique belge” que d’autres, à la suite de l’engouement de Maeterlinck pour Ruusbroec l’Admirable au début du siècle, voudront à leur tour raviver. On pense ici à Marc. Eemans et René Baert, qui, outre Ruusbroec (non considéré comme hérétique par les catholiques sourcilleux car il refusera toujours de dédaigner les “œuvres”), réhabiliteront Sœur Hadewijch, Harphius, Denys le Chartreux et bien d’autres figures médiévales (cf. Marc. Eemans, Anthologie de la Mystique des Pays-Bas, éd. de la Phalange / J. Beernaerts, Bruxelles, s. d. ; il s’agit des textes sur les mystiques des Pays-Bas publiés dans les années 30 dans la revue Hermès). R. De Becker se penchera également sur la figure de Ruusbroec, notamment dans un article du Soir, le 11 mars 1943 (« Quand Ruysbroeck l’Admirable devenait prieur à Groenendael »). Comme dans le cas du mythe bourguignon, inauguré par Luc Hommel (cf. supra) et Paul Colin, le recours à la veine mystique médiévale participe d’une volonté de revenir à des valeurs nées du sol entre Somme et Rhin, pour échapper à toutes les folies idéologiques qui secouaient l’Europe, à commencer par le laïcisme républicain français, dont la nuisance n’a pas encore cessé d’être virulente, notamment par le filtre de la “nouvelle philosophie” d’un marchand de “prêt-à-penser” brutal et sans nuances comme Bernard-Henri Lévy (classé récemment par Pascal Boniface comme « l’intellectuel faussaire », le plus emblématique).

Fidèle à son double engagement neutraliste et mystique, Jean Libert voudra œuvrer au relèvement moral et physique de la jeunesse, en prolongeant l’effet bienfaisant qu’avait le scoutisme sur les adolescents. Au lendemain de la défaite de mai 1940, J. Libert rejoint les Volontaires du Travail, regroupés autour de Henry Bauchau, Théodore d’Oultremont et Conrad van der Bruggen. Ces Volontaires du travail devaient prester des travaux d’utilité publique, de terrassement et de déblaiement, dans tout le pays pour effacer les destructions dues à la campagne des 18 jours de mai 1940. C’était également une manière de soustraire des jeunes aux réquisitions de l’occupant allemand et de maintenir sous bonne influence “nationale” des équipes de jeunes appelés à redresser le pays, une fois la paix revenue. Pendant la guerre, J. Libert collaborera au Nouveau Journal de Robert Poulet, ce qui lui vaudra d’être épuré, au grand scandale d’Hergé qui estimait, à juste titre, que la répression tuait dans l’œuf les idéaux positifs d’innocence, de spontanéité et de pureté (le “cœur pur” de Tintin au Tibet). Jamais le pays n’a pu se redresser moralement, à cause de cette violence “officielle” qui effaçait les ressorts de tout sursaut éthique, à coup de décisions féroces prises par des juristes dépourvus de “Sittlichkeit” et de culture. On voit les résultats après plus de 6 décennies...

Franz Weyergans

Parmi les adeptes du groupe de la “Capelle-aux-Champs”, signalons encore Franz Weyergans (1912-1974), père de François Weyergans. Lui aussi s’inspire de Saint François d’Assise. Il sera d’abord journaliste radiophonique comme Biebuyck. La littérature, pour autant qu’elle ait retenu son nom, se rappellera de lui comme d’un défenseur doux mais intransigeant de la famille nombreuse et du mariage. Weyergans plaide pour une sexualité pure, en des termes qui apparaissent bien désuets aujourd’hui. Il fustige notamment, sans doute dans le cadre d’une campagne de l’Église, l’onanisme.

Franz Weyergans est revenu sous les feux de la rampe lorsque son fils François, publie chez Grasset Franz et François une sorte de dialogue post mortem avec son père. Le livre recevra un prix littéraire, le Grand Prix de la Langue Française (1997). Il constitue un très beau dialogue entre un père vertueux, au sens où l’entendait l’Église avant-guerre dans ses recommandations les plus cagotes à l’usage des tartufes les plus assomants, et un fils qui s’était joyeusement vautré dans une sexualité picaresque et truculente dès les années 50 qui annonçaient déjà la libération sexuelle de la décennie suivante (avec Françoise Sagan not.). Deux époques, deux rapports à la sexualité se télescopent dans Franz et François mais si François règle bien ses comptes avec Franz — et on imagine bien que l’affrontement entre le paternel et le fiston a dû être haut en couleurs dans les décennies passées — le livre est finalement un immense témoignage de tendresse du fils à l’égard de son père défunt.

L’angoisse profonde et terrible qui se saisit d’Hergé dès le moment où il rencontre celle qui deviendra sa seconde épouse, Fanny Vleminck, et lâche progressivement sa première femme Germain Kieckens, l’ancienne secrétaire de l’Abbé Wallez au journal Le Vingtième siècle, ne s’explique que si l’on se souvient du contexte très prude de la “Capelle-aux-Champs” ; de même, son recours à un psychanalyste disciple de Carl Gustav Jung à Zürich ne s’explique que par le tournant jungien qu’opèreront R. De Becker, futur collaborateur de la revue Planète de Louis Pauwels, et Henry Bauchau dès les années 50.

Biebuyck et Weyergans, même si nos contemporains trouveront leurs œuvres surannées, demeurent des écrivains, peut-être mineurs au regard des critères actuels, qui auront voulu, et parfois su, conférer une “dignité à l’ordinaire”, comme le rappelle C. Vanderpelen-Diagre. Jacques Biebuyck et Franz Weyergans, sans doute contrairement à Tintin (du moins dans une certaine mesure), ne visent ni le sublime ni l’épique : ils estiment que “la vie quotidienne est un pèlérinage ascétique”.

De l’ACJB à Rex

Mais dans toute cette effervescence, inégalée depuis lors, quelle a été la genèse de Rex, du mouvement rexiste de Léon Degrelle ? Les 29, 30 et 31 août 1931 se tient le congrès de l’ACJB, présidé par Léopold Levaux, auteur d’un ouvrage apologétique sur Léon Bloy (Léon Bloy, éd. Rex, Louvain, 1931). À la tribune : Monseigneur Ladeuze, Recteur magnifique de l’Université Catholique de Louvain, l’Abbé Jacques Leclercq et Léon Degrelle, alors directeur des Éditions Rex, fondées le 15 janvier 1931. Le futur fondateur du parti rexiste se trouvait donc à la fin de l’été 1931 aux côtés des plus hautes autorités ecclésiastiques du pays et du futur mentor de la démocratie chrétienne, qui finira par se situer très à gauche, très proche des communistes et du résistancialisme qu’ils promouvaient à la fin des années 40. L’organisation de ce congrès visait le couronnement d’une série d’activités apostoliques dans les milieux catholiques et, plus précisément, dans le monde de la presse et de l’édition, ordonnées très tôt, sans doute dès le lendemain de la Première Guerre mondiale, par le cardinal Mercier lui-même. L’année de sa mort, qui est aussi celle de la condamnation de l’Action française par le Vatican (1926), est suivie rapidement par la fameuse “substitution de gourou” dans les milieux catholiques belges : on passe de Maurras à Maritain, du nationalisme intégral à l’humanisme intégral. En cette fin des années 20 et ce début des années 30, Maritain n’a pas encore une connotation de gauche : il ne l’acquiert qu’après son option en faveur de la République espagnole.

C’est une époque où le futur Monseigneur Picard s’active, notamment dans le groupe La nouvelle équipe et dans les Cahiers de la jeunesse catholique. En août 1931, à la veille de la rentrée académique de Louvain, il s’agit de promouvoir les éditions Rex, sous la houlette de Degrelle (c’est pour cela qu’il est hissé sur le podium à côté du Recteur), de Robert du Bois de Vroylande (1907-1944) et de Pierre Nothomb. En 1932, l’équipe, dynamisée par Degrelle, lance l’hebdomadaire Soirées qui parle de littérature, de théâtre, de radio et de cinéma. Les catholiques, auparavant rétifs à toutes les formes de modernité même pratiques, arraisonnent pour la première fois, avec Degrelle, le secteur des loisirs. La forme, elle aussi, est moderne : elle fait usage des procédés typographiques américains, utilise en abondance la photographie, etc. La parution de Soirées, hebdomadaire en apparence profane, apporte une véritable innovation graphique dans le monde de la presse belge. Les éditions Rex ont été fondées “pour que les catholiques lisent”. L’objectif avait donc clairement pour but de lancer une offensive “métapolitique”.

L’équipe s’étoffe : autour de Léon Degrelle et de Robert du Bois de Vroylande, de nouvelles plumes s’ajoutent, dont celle d’Aman Géradin (1910-2000) et de José Streel (1911-1946), auteur de 2 thèses, l’une sur Péguy, l’autre sur Bergson. Plus tard, Pierre Daye, Joseph Mignolet et Henri-Pierre Faffin rejoignent les équipes des éditions Rex. Celles-ci doivent offrir aux masses catholiques des livres à prix réduit, par le truchement d’un système d’abonnement. C’est le pendant francophone du Davidsfonds catholique flamand (qui existe toujours et est devenu une maison d’édition prestigieuse). Cependant, l’épiscopat, autour des ecclésiastiques Picard et Ladeuze, n’a pas mis tous ses œufs dans le même panier. À côté de Rex, il patronne également les Éditions Durandal, sous la direction d’Edouard Ned (1873-1949). Celui-ci bénéficie de la collaboration du Chanoine Halflants, de Firmin Van den Bosch, de Georges Vaxelaire, de Thomas Braun, de Léopold Levaux et de Camille Melloy. L’épiscopat a donc créé une concurrence entre Rex et Durandal, entre Degrelle et Ned. C’était sans doute, de son point de vue, de bonne guerre. Les éditions Durandal, offrant des ouvrages pour la jeunesse, dont nous disposions à la bibliothèque de notre école primaire (vers 1964-67), continueront à publier, après la mort de Ned, jusqu’au début des années 60.

Degrelle rompt l’unité du parti catholique

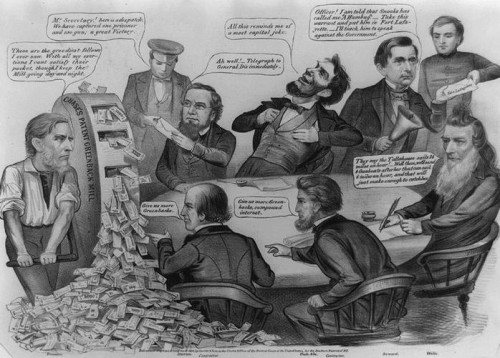

Léon Degrelle veut faire triompher son équipe jeune (celle de Ned est plus âgée et a fait ses premières armes du temps de la Jeune Droite de Carton de Wiart). Il multiplie les initiatives, ce qui donne une gestion hasardeuse. Les stocks d’invendus sont faramineux et les productions de Rex contiennent déjà, avant même la formation du parti du même nom, des polémiques trop politiques, ce qui, ne l’oublions pas, n’est pas l’objectif de l’ACJB, organisation plus culturelle et métapolitique que proprement politique et à laquelle les éditions Rex sont théoriquement inféodées. Degrelle est désavoué et Robert du Bois de Vroylande quitte le navire, en dénonçant vertement son ancien associé. Meurtri, accusé de malversations, Degrelle se venge par le fameux coup de Courtrai, où, en plein milieu d’un congrès du parti catholique, il fustige les “banksters”, c’est-à-dire les hommes politiques qui ont créé des caisses d’épargne et ont joué avec l’argent que leur avaient confié des petits épargnants pieux qui avaient cru en leurs promesses (comme aujourd’hui pour la BNP et Dexia, sauf que la disparition de toute éthique vivante au sein de la population n’a suscité aucune réaction musclée, comme en Islande ou en Grèce par ex.).

Léon Degrelle veut faire triompher son équipe jeune (celle de Ned est plus âgée et a fait ses premières armes du temps de la Jeune Droite de Carton de Wiart). Il multiplie les initiatives, ce qui donne une gestion hasardeuse. Les stocks d’invendus sont faramineux et les productions de Rex contiennent déjà, avant même la formation du parti du même nom, des polémiques trop politiques, ce qui, ne l’oublions pas, n’est pas l’objectif de l’ACJB, organisation plus culturelle et métapolitique que proprement politique et à laquelle les éditions Rex sont théoriquement inféodées. Degrelle est désavoué et Robert du Bois de Vroylande quitte le navire, en dénonçant vertement son ancien associé. Meurtri, accusé de malversations, Degrelle se venge par le fameux coup de Courtrai, où, en plein milieu d’un congrès du parti catholique, il fustige les “banksters”, c’est-à-dire les hommes politiques qui ont créé des caisses d’épargne et ont joué avec l’argent que leur avaient confié des petits épargnants pieux qui avaient cru en leurs promesses (comme aujourd’hui pour la BNP et Dexia, sauf que la disparition de toute éthique vivante au sein de la population n’a suscité aucune réaction musclée, comme en Islande ou en Grèce par ex.).

Degrelle, en déboulant avec ses “jeunes plumes” dans le congrès des “vieilles barbes”, a commis l’irréparable aux yeux de tous ceux qui voulaient maintenir l’unité du parti catholique, même si, parfois, ils entendaient l’infléchir vers une “voie italienne” (comme Nothomb avec son “Lion ailé”) ou vers un maritainisme plus à gauche sur l’échiquier politique, ouvert aux socialistes (notamment aux idées planistes de Henri De Man et pour mettre en selle des coalitions catholiques / socialistes) voire carrément aux idées marxistes (pour absorber une éventuelle contestation communiste). De l’équipe des éditions Rex, seuls Daye, Streel, Mignolet et Géradin resteront aux côtés de Degrelle : ils forment un parti concurrent, le parti rexiste qui remporte un formidable succès électoral en 1936, fragilisant du même coup l’épine dorsale de la Belgique d’après 1918, forgée lors des fameux accords de Lophem. Ceux-ci prévoyaient une démocratie réduite à une sorte de circuit fermé sur 3 formations politiques seulement : les catholiques, les libéraux et les socialistes, avec la bénédiction des “acteurs sociaux”, les syndicats et le patronat. Les Accords de Lophem ne prévoyaient aucune mutation politique, aucune irruption de nouveautés organisées dans l’enceinte des Chambres. Et voilà qu’en 1936, 3 partis, non prévus au programme de Lophem, entrent dans l’hémicycle du parlement : les nationalistes flamands du VNV, les rexistes et les communistes.

Toute innovation est assimilée à Rex et à la Collaboration

Les rexistes (en même temps que les nationalistes flamands et les communistes), en gagnant de nombreux sièges lors des élections de 1936, relativisent ipso facto les fameux accords de Lophem et fragilisent l’édifice étatique belge, dont les critères de fonctionnement avaient été définis à Lophem. Depuis lors, toute nouveauté, non prévue par les accords de Lophem, est assimilée à Rex ou au mouvement flamand. Fin des années 60 et lors des élections de 1970, des affiches anonymes, placardées dans tout Bruxelles, ne portaient qu’une seule mention : “FDF = REX”, alors que les préoccupations du parti de Lagasse n’avaient rien de commun avec celles du parti de Degrelle. Ce n’est pas le contenu idéologique qui compte, c’est le fait d’être simplement challengeur des accords de Lophem. Même scénario avec la Volksunie de Schiltz (qui, pour sauver son parti, fera son aggiornamento belgicain, lui permettant de se créer une niche nouvelle dans un scénario de Lophem à peine rénové). Et surtout même scénario dès 1991 avec le Vlaams Blok, assimilé non seulement à Rex mais à la collaboration et, partant, aux pires dérives prêtées au nazisme et au néo-nazisme, surtout par le cinéma américain et les élucubrations des intellectuels en chambre de la place de Paris.

Le choc provoqué par le rexisme entraîne également l’implosion du pilier catholique belge, jadis très puissant. Le voilà disloqué à jamais : une recomposition sur la double base de l’idéal d’action de Blondel (avec exigence éthique rigoureuse) et de l’idéal de justice sociale de Carton de Wiart et de l’Abbé Daens, s’est avérée impossible, en dépit des discours inlassablement répétés sur l’humanisme, le christianisme, les valeurs occidentales, la notion de justice sociale, la volonté d’être au “centre” (entre la gauche socialiste et la droite libérale), etc. Une telle recomposition, s’il elle avait été faite sur base de véritables valeurs et non sur des bricolages idéologiques à base de convictions plus sulpiciennes que chrétiennes, plus pharisiennes que mystiques, aurait permit de souder un bloc contre le libéralisme et contre toutes les formes, plus ou moins édulcorées ou plus ou moins radicales, de marxisme, un bloc qui aurait véritablement constitué un modèle européen et praticable de “Troisième Voie” dès le déclenchement de la guerre froide après le coup de Prague de 1948.

Cet idéal de “Troisième Voie”, avec des ingrédients plus aristotéliciens, grecs et romains, aurait pu épauler avec efficacité les tentatives ultérieures de Pierre Harmel, un ancien de l’ACJB, de rapprocher les petites puissances du Pacte de Varsovie et leurs homologues inféodées à l’OTAN (sur Harmel, lire : Vincent Dujardin, Pierre Harmel, Le Cri, Bruxelles, 2004). L’absence d’un pôle véritablement personnaliste (mais un personnalisme sans les aggiornamenti de Maritain et des personnalistes parisiens affectés d’un tropisme pro-communiste et craignant de subir les foudres du tandem Sartre-De Beauvoir) n’a pas permis de réaliser cette vision harmélienne d’une “Europe Totale” (probablement inspirée de Blondel, cf. supra), qui aurait parfaitement pu anticiper de 20 ans la “perestroïka” et la “glasnost” de Gorbatchev.

Une véritable implosion du bloc catholique

Le pilier catholique de l’après-guerre n’ose plus revendiquer expressis verbis un personnalisme éthique exigeant. Fragmenté, il erre entre plusieurs môles idéologiques contradictoires : celui d’un personnalisme devenu communisant avec l’UDB (où se retrouve un William Ugeux, ex-journaliste du Vingtième Siècle de l’Abbé Wallez, l’admirateur sans faille de Maurras et de Mussolini !), qui, après sa dissolution dans le désintérêt général, va générer toutes les variantes éphémères du “christianisme de gauche”, avec le MOC et en marge du MOC (Mouvement Ouvrier Chrétien) ; celui du technocratisme qui, comme toutes les autres formes de technocratisme, exclut la question des valeurs et de l’éthique de l’orbite politique et laisse libre cours à toutes les dérives du capitalisme et du libéralisme, provoquant à terme le passage de bon nombre d’anciens démocrates chrétiens du PSC, ceux qui confondent erronément “droite” et “libéralisme”, dans les rangs des PLP, PRL et MR libéraux ; le technocratisme fut d’abord importé en Belgique par Paul Van Zeeland, immédiatement dans la foulée de sa victoire contre Rex, lors des élections de 1937, provoquées par Degrelle qui espérait déclencher un nouveau raz-de-marée en faveur de son parti.

Van Zeeland avait besoin d’un justificatif idéologique en apparence neutre pour pouvoir diriger une coalition regroupant l’extrême-gauche communiste, les socialistes, les libéraux et les catholiques. Les avatars multiples du premier technocratisme zeelandien déboucheront, dans les années 90, sur la “plomberie” de Jean-Luc Dehaene, c’est-à-dire sur les bricolages politiciens et institutionnels, sur les expédiants de pure fabrication, menant d’abord à une Belgique sans personnalité aucune (et à une Flandre et à une Wallonie sans personnalité séduisante) puis sur une “absurdie”, un “Absurdistan”, tel que l’a décrit l’écrivain flamand Rik Vanwalleghem (cf. supra). Enfin, on a eu des formes populistes vulgaires dans les années 60 avec les “listes VDB” de Paul Van den Boeynants qui ont débouché au fil du temps dans le vaudeville, le stupre et la corruption. Autre résultat de la mise entre parenthèse des questions axiologiques ou éthiques...